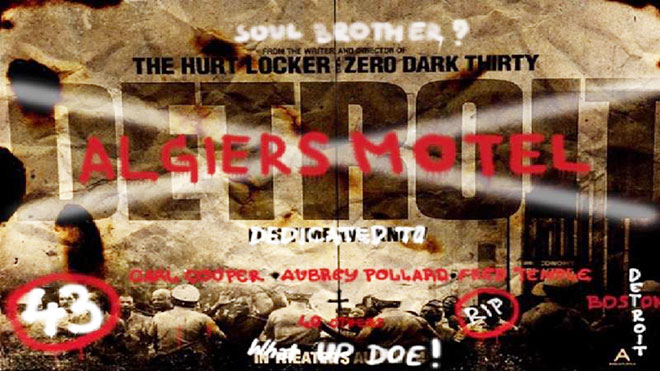

Earlier this month, the film “Detroit” opened in theatres all across the United States. Produced by Academy Award-winning director Kathryn Bigelow and writer Mark Boal, the movie was right on time for the 50th anniversary of the historic 1967 Rebellion.

The 30-million-dollar film starts with a convincing depiction of what triggered the unrest and moves quickly to the city’s Algiers Motel, where three black men were murdered by police officers. The officers responsible for the killings were later acquitted.

The spark that set the fire of rebellion was the busting of an after-hours joint – a blind pig – in the heart of a black neighbourhood. The community swiftly responded to the raid: Detroit burned for five days, 43 people died, 1,189 people were injured, over 7,000 were arrested and more than 2,000 buildings were destroyed. The national guard was brought in. It was a catastrophe that would change the city forever.

Inspired by the 50th anniversary of the rebellion, I came home to Detroit this past Memorial Day to present my annual Burn and Bury Memorial ritual – a mock funeral for and cremation of the Confederate flag featuring some of the city’s finest poets and activists – to an audience gathered at the N’Namdi Gallery. The ceremony took place a few weeks before the official commemoration of the 1967 rebellion, which included a full programme of events led by the Detroit Historical Society, Wright Museum, and Detroit Institute of Arts, demonstrating how special the anniversary is for Detroit.

And since I was in Detroit and in utero during the summer of 1967, this time in history is particularly meaningful to me – the stories, the burned out remains, the pain, the expression, and the need to resist and rebel against the historical gravity of American white supremacy. And so, I was very excited to see this movie.

My excitement about Bigelow’s “Detroit” was quickly eclipsed once I got past its beautiful and powerful opening scene, which features lightly animated variations on Jacob Lawrence’s painting series on the Great Migration. And by the time the film ended, I felt like I had watched a mash-up of Get Out, Five Heartbeats, and the most brutal parts of 12 Years a Slave.

The film was not really about the complex factors and stories that led to and sustained five days of activity. It was a sub-narrative dramatisation of mass murder and psychological pathos about what happened in a motel – a worthy of story and film all by itself. And the film works better this way, if the expectations were restricted to this important story.